________________________________________________________

だいがくせいじゃありません。せんせいです!

Daigakusei ja arimasen. Sensei desu!

I am not a student. I am a teacher!

Verb 'to be' in the negative form

In our last lesson, we saw our first verb in Japanese, the verb です (desu), which is the verb 'to be'.

We also saw that verbs do not change according to the pronouns, like it is the case in French or in English with the third person singular pronoun. The verb endings will only change when we change tenses or if we speak in different keigo or familiarity levels.

Now, it is time to learn how to transform this verb into the negative form as this will become handy to you if ever someone is wrong about your name or your profession.

To say the verb 'to be' in the negative form, simply change です (desu) to じゃありません (ja arimasen.) You will notice that a lot of verbs in Japanese end in 〜ます (〜masu) for the affirmative and 〜ません (〜masen) for the negative.

There is another way to say the negative form of です (desu) and it is ではありません (dewa arimasen), which is a littler bit more polite.

Excuse-me, are you Panda-sensei?

すみません、パンダせんせいですか?

Sumimasen, Panda-sensei desu ka?

No, I am not Panda-sensei. I am only a student.

いいえ、パンダせんせいじゃありません。がくせいだけです。

Iie, Panda-sensei ja arimasen. Gakusei dake desu.

In this sentence, だけ (dake) means 'only.' You can see that, in the case of the negative, the sentence structure is the exact same as in the affirmative. So, in the case of simple sentences with the verb です (desu), the affirmative, negative and question sentences have the same order.

Excuse-me, are you Naoko-san?

すみません、なおこさんですか?

Sumimasen, Naoko-san desu ka?

No, I am not Naoko. I am Emi.

いいえ、なおこじゃありません。エミです。

Iie, Naoko ja arimasen. Emi desu.

Are you an engineer?

エンジニアですか?

Enjinia desu ka?

No, I am not an engineer. I am an office worker.

いいえ、エンジニアじゃありません。かいしゃいんです。

Iie, enjinia ja arimasen. Kaishain desu.

So, the verb 'desu' in the negative becomes 'ja arimasen'. Keep in mind that the verb 'to be' is totally irregular in Japanese.

________________________________________

Hiragana Table

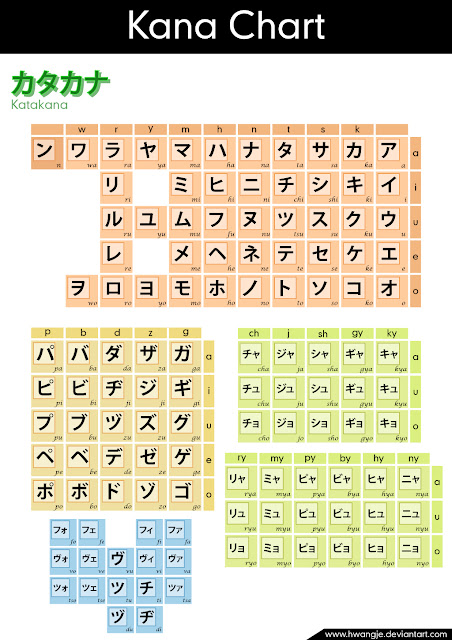

It is time already to make you study those hiragana! Hiragana are the first characters that we learn as children and they are far easier than katakana. Technically speaking, once you learn the hiragana, you will be able to write in Japanese completely.

The Japanese alphabet is composed of consonant-vowel syllables, which make Japanese easy to pronounce. There are 46 hiragana for the 46 basic syllables.

For certain sounds, Japanese add either tenten or maru, which are small symbols on top of the hiragana to make another sound. You can see that the hiragana in the centre of the graph below, which make a g, a z, a d and a b-sound, use the tenten (these two small strokes on top of the hiragana) and the hiragana below them, which make a p-sound, use the maru (the small circle on top of them.)

On the right-hand side, these are what we called complex syllables, which will use either a small や (ya), ゆ (yu) or よ (yo), combined with the syllable i to make complex sounds like kya, kyu, kyo, sha, shu, sho, cha, chu, cho, etc.

Writing conventions and rules

Once you have memorised and remembered these hiragana, you are not done yet. You still have to learn some writing rules. Learning these characters is yet not enough to be able to read or write in Japanese. There are some writing rules you need to remember.

You've already probably seen that there is no space between words when writing in Japanese. It's true. We don't space up words. It might be a little difficult for you at first to distinguish words in a sentence, but the more vocabulary you know, the more you will be able to pinpoint words. And of course, kanji is also good for this, as particles will often separate words and we write particles in hiragana, so all kanji forming a word will be separated by particles.

Long vowels

In Japanese, we make a distinction between short and long vowels. This is important to note, because if you do not make this distinction, you could say a different word than what you actually want to say.

Take these two words for instance: obasan and obaasan. Obasan is aunt and obaasan is grandmother or an old woman. Now, you really don't want to mix these two up, do you?

Each vowel can be an elongated, a, i, u, e and o.

For the vowels a, i and u, you simply add another a, i or u to make the sound longer.

おばさん = おばあさん (aunt = grandmother, old woman)

おじさん = おじいさん (uncle = grandfather, old man)

すり = すうり (pickpocket = mathematical principle)

For a longer e, you add i to make the sound longer.

えき = えいき (station = energy, spirit)

てき = ていき (enemy = commuter ticket)

Note that this is not pronounced 'e-i', but 'ee'.

*There are some exceptions to this rule.

おねえさん (older sister)

ええ (yes, in a slang way)

いいですねえ (it's good, isn't it?)

For a longer o, you add u to make the sound longer.

も = もう (also = already)

ほ = ほう (sail = law)

These words will be pronounced mo-o and ho-o, not mo-u and ho-u. The only time you actually pronounce the u following an o is with verbs (i.e. omou will be pronounced omo-u.)

*There are some exceptions to this rule as well.

おおきい (big)

こおり (ice)

とおり (street)

おおさか (Osaka city)

Consonant break

Consonant break occurs when there is a double consonant, such as in the words gakkou, icchi, motto, shitto, etc. Consonant breaks are represented by a mini つ.

がっこう (school)

いっち (one family)

もっと (more)

しっと (jealousy)

There will be a little pause in between ga and kou, i and chi, mo and to, and shi and to. If you do not make that pause, you will say a different word.

いき = いっき (breath = riot)

はかい = はっかい (destruction = 8th floor)

べし = べっし (must, command = contempt)

So, be mindful when you pronounce certain words. Remember to pronounce long vowels and consonant breaks properly, otherwise you will be saying something completely different. Japanese people are very sensitive to hearing those differences.

Pitch accent

Pitch accent is not a big concern when it comes to learning Japanese, but I would like to talk about it since a lot of Japanese words are pronounced and written the same way. This is when kanji come in handy to differentiate these words. Take a look at these words for instance...

あめ (雨) = rain

あめ (飴) = sweets

しろ (白) = white

しろ (城) = castle

The pitch will determine which word you are saying. However, due to the context, we will be able to determine what you are saying, even if you don't have the right pitch accent.

The pitch accent, as I mentioned, is not a concern, only if you really want to sound like native speakers. But it is possible that pitch accents might change depending on the dialects as well. So, I would not really worry about it too much.

__________________________________________

Goodbye - Sayounara (really dramatic, we don't use it to say 'bye')

See you soon - Mata (ne) (*you can add 'ne' if you want)

See you tomorrow - Mata ashita

Excuse-me - Shitsurei (shimasu) (when you excuse yourself from something)

You're welcome - Douitashimashite (*not really used), douzo (yoroshiku onegaishimasu)

No, really, it's not like that - sonna koto arimasen (when receiving a compliment)

Yes - Hai

No - Iie

Welcome - Irrashaimase (when entering a shop), youkoso (general welcome), okaerinasai (when returning home)

I'm home - Tadaima

Sorry to disturb - Ojama shimasu (when entering somebody's home)

I'm going - Ittekimasu (when going out of the house)

Take care - ki o tsukete (ne), itterasshai (when someone is departing)

Sorry to keep you waiting - Omatase (shimashita)

Thank you for your time - Otsukaresama (deshita)

Hurry up - Isoide (kudasai)

It's okay - Daijoubu (desu)

I did it! - Yatta!

I am done - Dekimashita (polite form), dekita (casual form)

___________________________________________________________

You have completed lesson 2!

レッシュン2ができました!

Resshun 2 ga dekimashita!